A lot of Google Shopping or Performance Max campaign structures are unnecessary or outright hurt your performance. I see it all the time: an account is either running one campaign when it should have three, or it’s running ten campaigns when it only needs two. The entire reason to segment Shopping campaigns is simple: to help Smart Bidding perform better.

Smart Bidding is powerful, but it can’t see ahead. It doesn’t know a product went on sale yesterday, which changes everything about how that product will perform today. It doesn’t understand the strategic value of one product category over another. That’s where a thoughtful campaign structure comes in. It’s not about complexity; it’s about control and context.

This article will walk you through seven campaign structures that work, four that don’t, and a concrete example of how we analyze our way to a new structure. This way, you can build a structure based on your own data instead of just copying whatever sounds good on LinkedIn.

A quick note: I’m talking about Shopping campaigns here, but these same principles apply directly to Performance Max. Personally, I’m a bigger fan of Standard Shopping, but that’s a topic for another day. The logic is the same.

Go Beyond the Article

Why the Video is Better:

- See real examples from actual client accounts

- Get deeper insights that can’t fit in written format

- Learn advanced strategies for complex situations

Why Bother with Campaign Structure in an Era of Smart Bidding?

The primary purpose of creating more than one Shopping campaign is to give Smart Bidding a helping hand. As mentioned, its biggest fault is that it’s purely reactive. If a product suddenly goes on sale, it will start converting better. When the sale ends, it will stop performing as well. By structuring products into separate campaigns, we can give Smart Bidding crucial context it wouldn’t have otherwise.

The secondary purpose is to enable different campaign-level settings. Creating different campaigns for different product groups allows you to change settings to nudge Smart Bidding in the right direction. You can adjust:

- Campaign priorities

- Negative keywords

- Product selection

- Bidding targets (ROAS/tCPA)

- Budgets

The entire idea is that segmentation, when done correctly, gives you the levers to improve performance. The problem is that we often oversegment, thinning out the data and making things worse.

The Pre-Flight Check: 2 Rules Before You Segment Anything

Before you even think about building an advanced structure, you need two things in place. These are non-negotiable.

Rule #1: Always Split Brand vs. Non-Brand

This should be your first and most foundational split. It should serve as the underlying structure for any other segmentation you add later. Brand search intent and performance are so fundamentally different that they must be isolated. In my opinion, your brand traffic should always be in a separate campaign.

Rule #2: A Minimum of 100 Conversions Per Campaign

This is my rule, not Google’s. Google talks about 15 conversions in 30 days, but that’s just the minimum to get access to Smart Bidding. It is absolutely not the level where it performs best. For a campaign to have enough data to be managed effectively by Smart Bidding, I want to see at least 100 conversions per month.

If you split your products and a new campaign won’t hit that threshold, you risk it performing worse simply because there isn’t enough data. You’re better off leaving all your products in one campaign. You can slightly mitigate this by using portfolio bid strategies to pool conversion data across several campaigns, but if you aren’t doing that, you must adhere to this rule.

There are a couple of exceptions. If you’re isolating low-performing products in a “saboteur” campaign just to limit spend, or isolating seasonal products before peak season to push them with a lower ROAS target, then those campaigns don’t need to hit the 100-conversion mark.

The Analyst’s Framework: How to Justify a New Campaign Structure

Before you start creating a complex campaign structure, you need to ask yourself one question: what are you trying to solve? I’ve seen countless advertisers get lost discussing a campaign split without ever asking if it actually makes sense for their business. You need a data-driven reason to act.

What Are You Trying to Solve?

To justify a split, you need one of two things to be true:

- There is a significant performance difference between the product segments you’re considering.

- You need to set a significantly different ROAS target or budget for the new segment.

My minimum for a “significant difference” in targets is 20%. Creating one campaign with a 600% ROAS target and another with a 650% target is pointless. It just splits the data, thins out what Smart Bidding can learn, and accomplishes nothing.

The Data You Need to Analyze (Hint: It’s Conversion Rate)

Before you build anything, create the segmentation you’re considering in your data. Use custom labels or backend data to pull a report and analyze the core metrics: conversion rate, ROAS, and CPC. If you want to split out pants and shorts, look at the historical performance of both groups.

While ROAS is important, I focus heavily on conversion rate. Why? Because ROAS will naturally fluctuate around your target. If you set a 600% ROAS goal, Google will work to hit that, masking the underlying performance differences. Conversion rate, however, tells a clearer story. It shows you the true difference in user behavior between two segments.

If you don’t have the historical data (for instance, for a “products on sale” label you just created), then you have to wait. Let the custom label populate for 2 to 12 weeks, then analyze the results. Don’t create a split based on a guess.

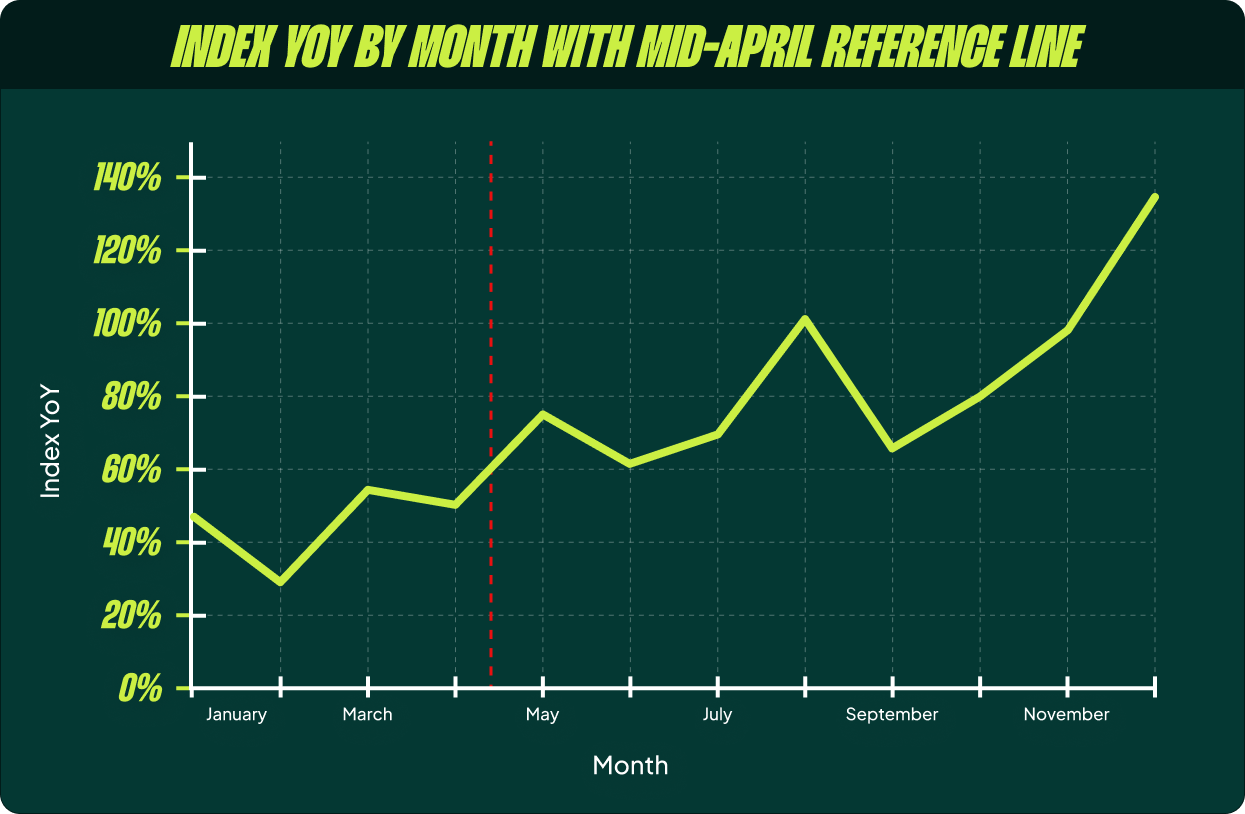

A Real-World Example: Analyzing Our Way to a New AOV Split

Here’s a practical case from one of our accounts. We had been battling rising CPCs for a year. We implemented an aggressive max bid limit, which successfully stopped the decline and got profit back on track. However, we had doubts about this structure going forward.

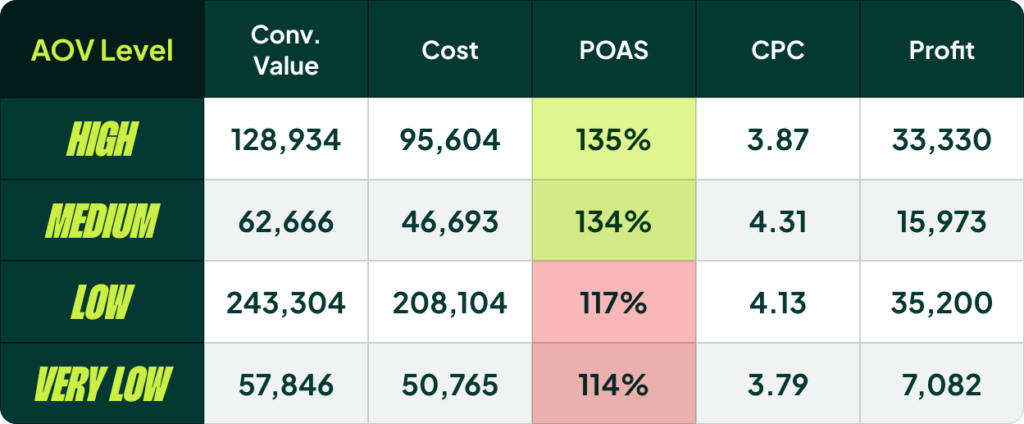

Our hypothesis was that the aggressive max bid limit was choking the exposure of our higher AOV products, which naturally have higher (and justifiable) CPCs. So, we did an analysis. We segmented all products into high, medium, low, and very low AOV buckets.

The data was clear: the POAS (Profit on Ad Spend) for high and medium AOV products was 135, while the POAS for low and very low AOV products was nearly identical. This suggested we were limiting our high-AOV products and potentially overexposing our low-AOV products.

This analysis gave us a clear thesis for our next test: Will separating high AOV products into their own campaign with a higher max bid limit result in more volume and profit from those products, while protecting the efficiency of our lower AOV products?

Behind every single campaign segmentation you create, there must be a question you are trying to answer.

7 Proven Shopping Campaign Structures That Actually Work

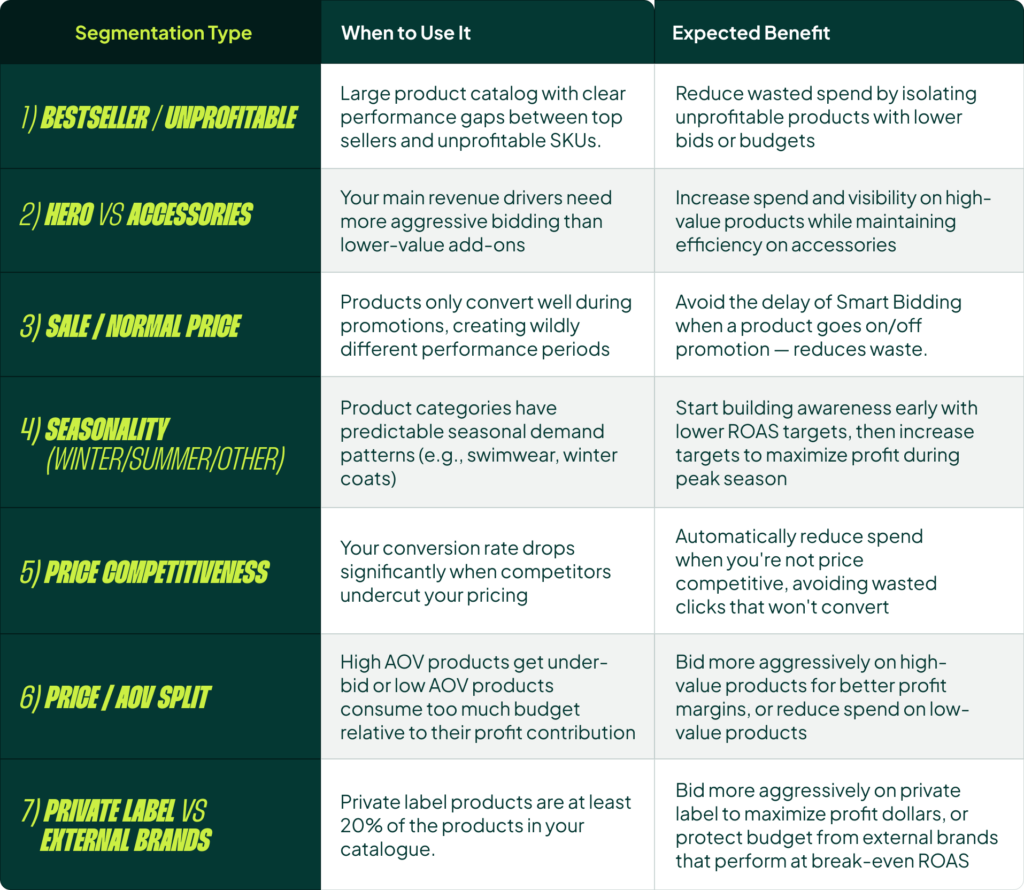

Now that you have the framework, here are some practical segmentation ideas that are grounded in real performance drivers.

1. Bestseller vs. Unprofitable

This is a classic. It’s ideal for large product catalogs with clear performance gaps. The goal is to reduce wasted spend by isolating products that Smart Bidding spends a little on but never convert. By putting bestsellers in a high-priority campaign, you tell Google to show them first if multiple products match a search term.

2. Hero vs. Accessories

Imagine you sell mattresses (hero products) and mattress covers (accessories). The mattress is your main revenue driver and needs aggressive bidding. You don’t want the performance of your low-priced accessories interfering with the bidding on your core products.

3. Sale vs. Normal Price

A simple but effective split. Products on sale have a fundamentally different conversion rate and require a different ROAS target. Separating them allows you to manage this dynamically.

4. Seasonality

An underused but powerful split. Think swimwear, winter coats, or sandals vs. boots. By splitting them, you can build awareness early in the season with lower ROAS targets and then increase targets to maximize profit during peak season. Relying on Smart Bidding alone often means you miss the start of the season and aren’t profitable enough at the end.

5. Price Competitiveness

If you are tracking competitor pricing, you can segment products based on whether you are priced higher, lower, or at parity. This allows you to bid more aggressively when you know you have a price advantage.

6. Price/AOV Split

As described in my example, this is for when different price points have significantly different performance profiles and require different bidding logic to maximize overall profit.

7. Private Label vs. External Brands

If private label products are a meaningful part of your catalog (I’d say at least 20%), this split is a must. Private label products should have a better margin, so you can bid more aggressively on them to maximize profit dollars and protect your budget from lower-margin external brands.

4 Common Campaign Structures That Outright Hurt Performance

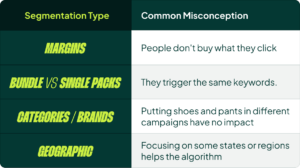

Just as important as knowing what to do is knowing what to avoid. I regularly see these four segmentation types, and they are almost always a mistake.

1. Margins

This sounds logical, but it fails in practice. The problem is that people don’t always buy what they click on. You might bid more for a high-margin product, only to have the user navigate to your site and buy a low-margin product instead. The attribution gets messy, and the strategy falls apart.

2. Product Variations (Bundles, Colors, Sizes)

Splitting out single packs vs. bundles, or different colors of the same shirt, is a bad idea. They trigger the same keywords and are competing for the same user. This needlessly complicates the account and provides no real benefit to Smart Bidding.

3. Categories & Brands

Simply putting “shoes” in one campaign and “pants” in another has no impact unless there is a dramatic performance difference between the two and you plan to manage them differently. Segmenting just for the sake of organization is counterproductive.

4. Geographic Location

This is a common one for businesses expanding into new, large markets (like Europeans coming to the US and splitting by state). This is not how Google Ads works. You can use location bid adjustments if needed, but a full campaign split by geography rarely makes sense for e-commerce and has never worked for anybody I’ve seen.

The Danger of Over-Segmentation: How to Combine Structures The Right Way

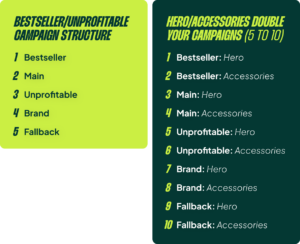

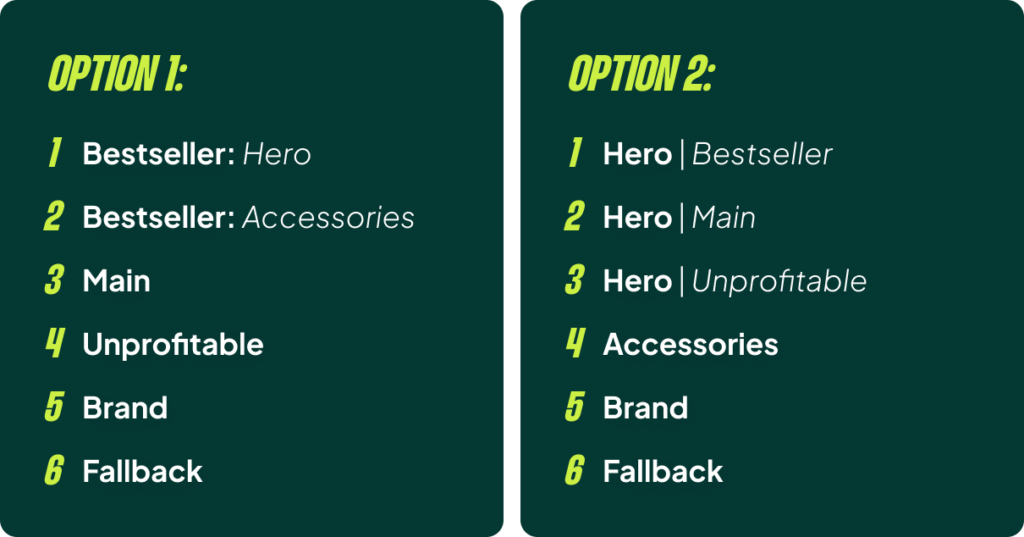

Most of the time, you should not fully combine campaign segmentation ideas. If you run a Bestseller structure (which might have 3-5 campaigns) and then add a Hero vs. Accessories split on top of that, the number of campaigns doubles from 5 to 10. The complexity increases exponentially, and you split your data so thin that Smart Bidding performance suffers.

Even though you might think this gives you more control, it’s needlessly complicated. You won’t be making significant changes between many of those granular campaigns.

The right way to combine structures is to be strategic. Instead of multiplying everything, you make a targeted split. For instance, you could take yourting Bestseller campaign and split only that campaign into Hero and Accessories. Or, you could pull all Accessories into their own standalone campaign and leave the rest of your products in a Bestseller/Main/Unprofitable structure. This keeps the structure manageable and ensures each campaign still has enough data.

How to Validate Your New Structure (Without Lying to Yourself)

Once you implement a new structure, you have to validate that it’s working. And as I said before, ROAS isn’t the best metric for this. You need to look at whether the conversion rate differences you predicted are actually materializing. The products in your Bestseller campaign should have a much higher conversion rate than the products in your Main or Unprofitable campaigns. If they don’t, the split isn’t working.

Most importantly, give it time. A good Google Shopping campaign structure needs 3 to 12 months to show its full value. Smart Bidding needs to learn, and you need to go through different business cycles. If you sell swimwear, you really need a full year to validate if a seasonal split works.

If a campaign structure is not delivering the expected benefit, consolidate back to a simpler setup. This is the most important takeaway. Do not stick with a complex structure that doesn’t add value. In that case, a single campaign will perform better.

[TL;DR]

- Start with a baseline. Use one campaign, perhaps with a brand split, and only expand from there.

- Analyze before you act. Use your own data to find meaningful differences in conversion rate or other core metrics before building a new structure.

- Require significant differences. Only split if there are major gaps in performance or if you need to set ROAS targets that differ by at least 20%.

- Ensure enough data. Each new primary campaign should be able to get at least 100 conversions per month.

- Have a clear hypothesis. Know what question you are trying to answer with your new structure.

- Validate over time. Give a new structure 3-12 months to prove its value. If it doesn’t, simplify your account again.