Intro

Just like YouTube Ads shouldn’t defacto be run by your Google Ads agency (unless they know what they’re doing), it’s equally wrong to classify branded and non-brand keywords as the same.

Just because they’re both within a Google Ads account does not mean they should be treated the same.

In this article, I explain why I believe nobody can agree on whether brand bidding is something you should or should not do and list some simple scenarios you can apply.

Let’s start with stating a fact:

If competitors are bidding for your brand term and you are not, you will lose revenue. We’ve run this test many times, but it doesn’t mean that you’ll always lose revenue if you’re not bidding for branded terms.

Different scenarios call for different actions. Competitors bidding for your brand? Then you probably should, too. Just you? Then you don’t have to. And then there are the gray areas.

Let’s get into it.

Nobody Agrees. Here’s Why.

We all have unique situations:

- Wholesale DTC brand? Your brand term is different and should be treated like any other mid-funnel keyword.

- No competition for your brand? You get little value (if any) from bidding on your brand besides paying a tax to Google.

- Well-known brand? You might spend your entire budget only on branded terms that drive very little incremental value (more on this in a second).

- Lots of competition for your brand term? Experiment with increasing/decreasing/removing your brand bidding.

- How unique is your brand term? We’ve worked with eCommerce stores with generic names like Cheap Fitness, InkCartridges, etc. This changes the underlying ability to decide not to bid for a brand term.

So, how can we arrive at a universal approach to discussing branded terms?

For that, we kept looking at the data until we found a singular question that is much better than, “Should I be bidding for my brand?”

The Better Question: Is Brand Bidding Incremental for My Brand?

First, let’s explain what incremental actually means.

The consensus is that the meaning of incremental is:

The measurement of the extra revenue attributable to an advertising effort beyond what would have occurred without it.

Said in layperson’s terms for this purpose: Incremental means whether a conversion would have happened whether we ran brand bidding or not.

And that’s where all the confusion lies because what’s incremental for one eCommerce brand is not incremental for another.

The reason for this is that your brand term might be bottom, middle, or top funnel:

- BOFU: Smaller DTC brand → Think Clutch Chargers.

- MOFU: Mid-sized brand → Think Huel

- TOFU: Large brand → Think Nike

The smaller you are, the more chances you’ll have for a brand search after exposure to Meta or Google Ads.

The bigger your brand is (and this ties directly to omnichannel presence, too), the more likely it is that your brand was recognized through logo or word of mouth.

The confusion, then, increases exponentially when I say that your ‘brand term’ has a different meaning for different people. For some, it’s BOFU because they were already in your funnel.

For others, it’s TOFU because they saw your logo on a friend’s t-shirt and were curious.

Now, let’s add another layer to the discussion:

The Deeper Question: Do You Need Brand Bidding?

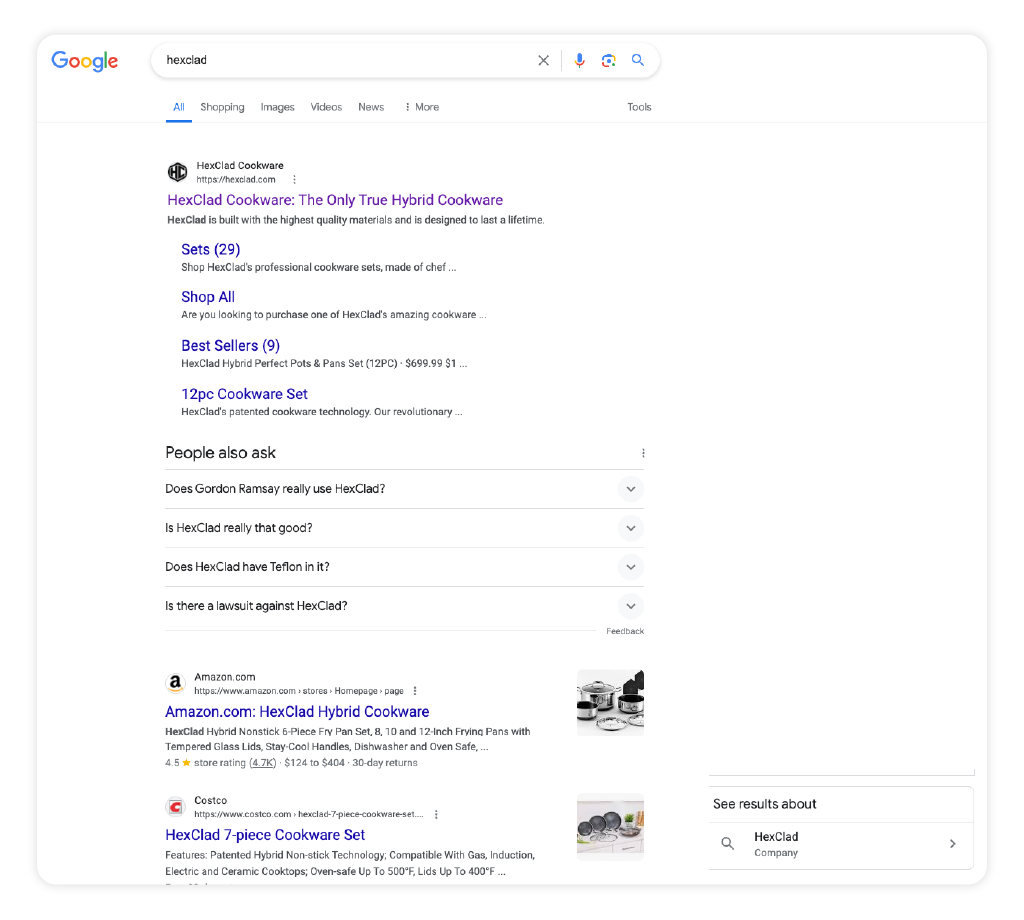

On a perfect Google search results page, you’d see this:

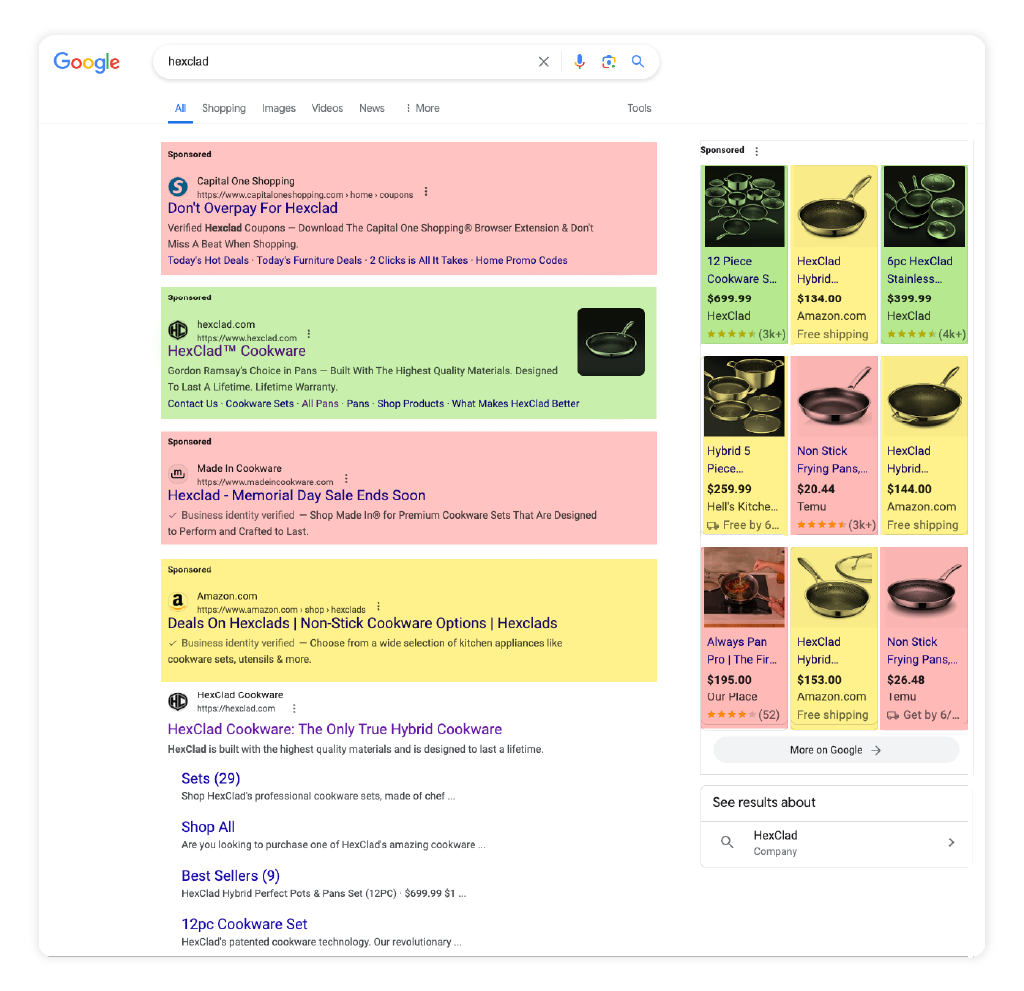

What we get instead is an assault on the consumer from different angles:

- Red = Affiliates & Competitors

- Capital One isn’t even a Hexclad affiliate. They’re an Amazon affiliate. God, I hate them.

- Yellow = Marketplaces & wholesale partners that sell Hexclad. Fair game.

- Green = Hexclad properties.

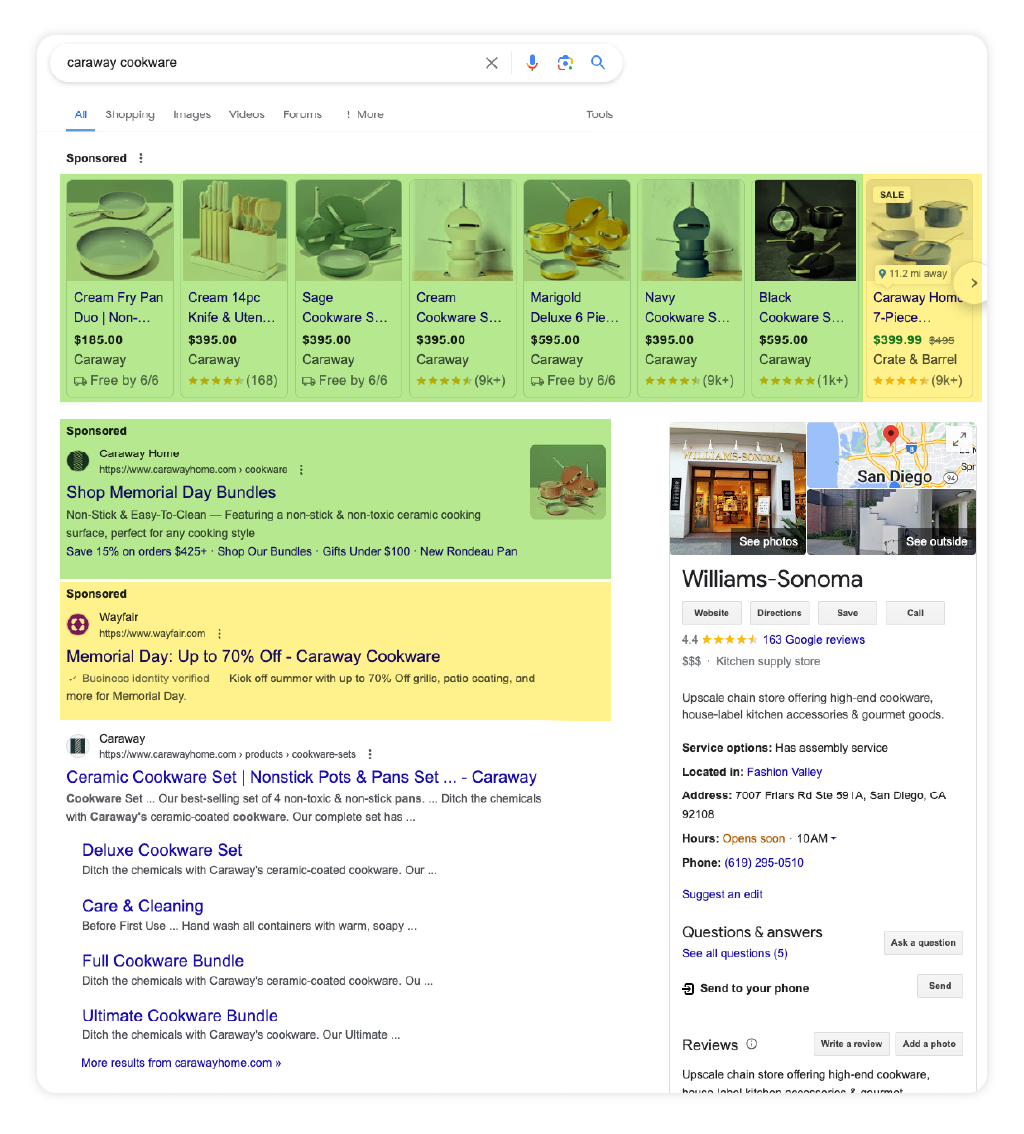

Let’s compare the Hexclad page to the Caraway page (a similar DTC cookware brand):

- No affiliate attacks.

- No competitor attacks.

These are two very similar DTC brands:

- Hexclad is bigger

- Both have an omnichannel presence (Hexclad more)

- Same industry → Cookware

- Same channel → DTC

However, there are very different brand results, and as such, both brands need different brand bidding strategies.

This is why we can’t agree: even fairly similar brands have completely different experiences.

Again, there isn’t one answer, but we have to go back to three different scenarios:

- Competition for your brand term? You should be bidding.

- Selling to wholesale that you compete with? You should be bidding aggressively.

- No competition for your brand term? No bidding necessary.

The caveat to the last scenario is that you might not catch competitors doing brand bidding until it’s too late.

Google’s broad match, Performance Max, and more will have your competitors bidding for your brand even if they didn’t outright choose to do so.

Note: I’m cautiously optimistic about Google’s brand profile, which they announced during Google Marketing Live 2024.

This might help tremendously with avoiding brand creep on their search pages, but I’m not holding my breath.

CPCs in Countries Are Different (Skip if you want)

In Europe, we can generally get brand terms for less than $0.2, and in many cases, we’re closer to $0.05-$0.08. It’s incredibly cheap.

In the US, such low prices are hard to find. (I might even say it’s impossible.)

So again, when you read advice or talk to people who say that you DEFINITELY have to bid for your brand or should NEVER bid for brand terms, find out where they’re coming from.

Are they paying $1+ for brand terms that are racking up a $10-20-50k bill per month? I’ve seen it (and higher).

That’s different from spending $0.05 per click and paying less than $2,000/mo. for the insurance of knowing competitors can’t just come in and start sucking up your brand terms.

Bidding Methodology: Manual or Smart Bidding?

Let’s summarize what we know:

- Not all brand bidding is incremental.

- Not all brand bidding costs the same.

With these two things in mind, let’s now look at how to approach brand bidding.

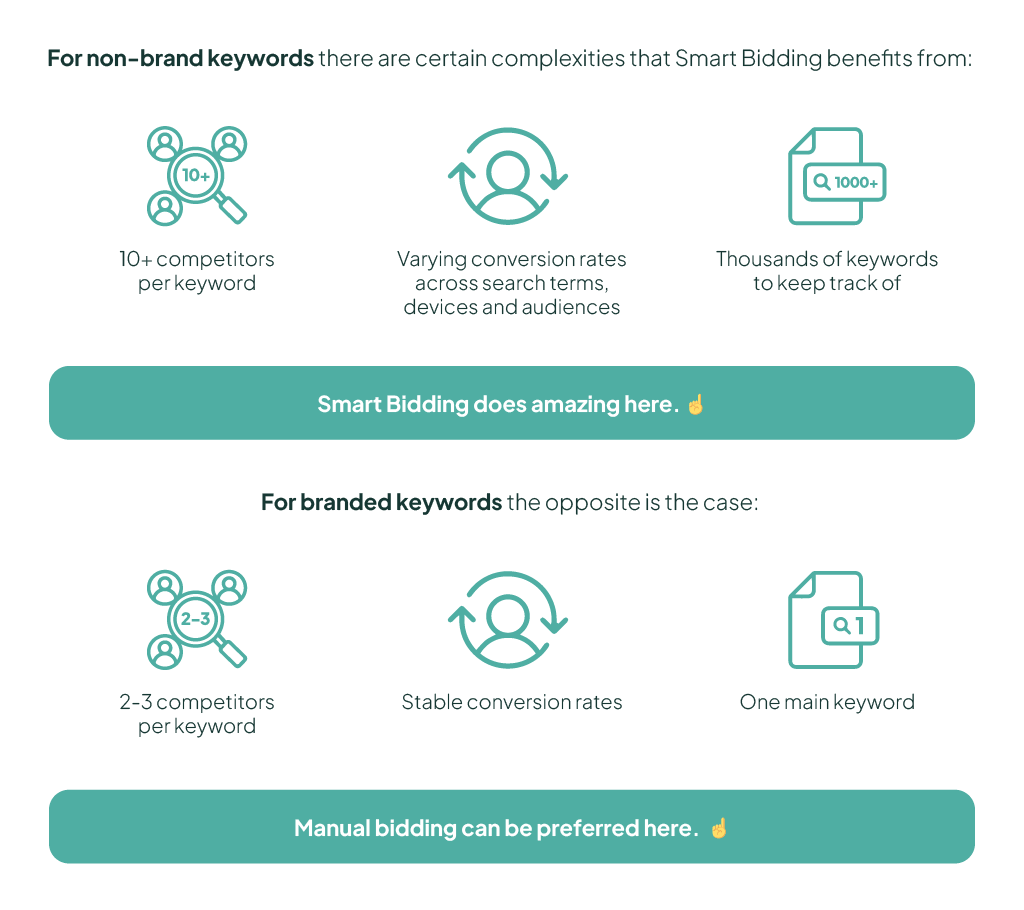

For non-brand keywords, there are certain complexities that Smart Bidding benefits from:

- 10+ competitors per keyword

- Varying conversion rates across search terms, devices, and audiences

- Thousands of keywords to keep track of

Smart Bidding does amazing here.

For branded keywords, the opposite is the case:

- Two to three competitors per keyword

- Stable conversion rates

- One main keyword

Manual bidding can be preferred here.

In my experience, Smart Bidding does fine if you set the Target ROAS sufficiently high, but personally, I always get better results with the tighter control I gain while using manual bidding.

The benefits from Smart Bidding are negligible when you only have one keyword to keep track of. Furthermore, if a few potential clients are lost due to a too-low bid, it’s likely that the sale isn’t lost because the brand bid isn’t incremental, as we discussed above.

But does that mean you should always use manual bidding for all brand bidding scenarios?

No.

If your brand keyword shares the complexities that make Smart Bidding efficient, then it might be better to run Smart Bidding.

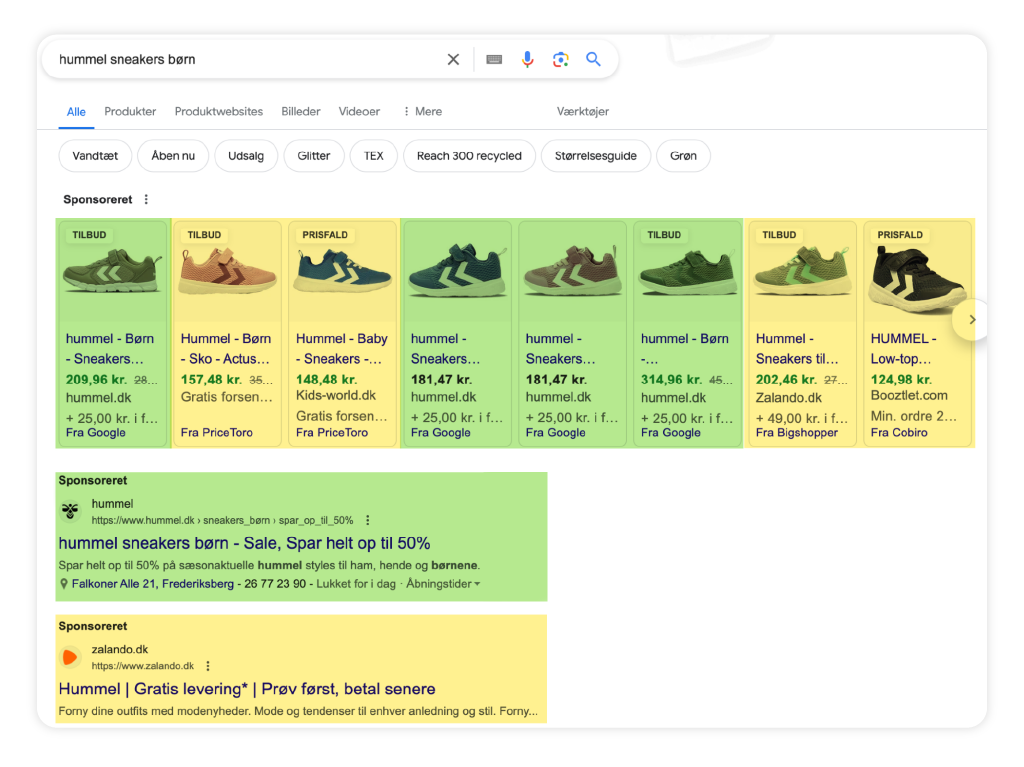

An example that comes to mind is when a DTC brand also has a big wholesale footprint and a lot of SKUs (apparel fits well here). Let’s take the Danish brand Hummel as an example.

Hummel sells:

- Thousands of products

- Has four to five competitors that sell the exact same products

In such a case, I’d bet that Smart Bidding would do better than manual bidding for their Shopping Ads.

The reason for this is that the complexity of maneuvering the right bid for the right product might be difficult to do manually.

So, if we recommend manual bidding for branded keywords, it’s usually when complexity is low. Otherwise, we still take advantage of the benefits that come with Smart Bidding.

Four Brand Bidding Tactics

I have four main tactics I’d like you to consider:

- Use Experiments to test bidding levels

- Be on the lookout for affiliates (aggressively)

- Campaign structure for brand bidding

- Brand and non-brand ROAS should never be aggregated

1) Use Experiments to Test Bidding Levels

When was the last time you ran an experiment instead of just changing your ROAS target to a CPC bid?

In my opinion, the experiments feature in Google Ads is not used enough. You can get some great insights when changing ROAS targets and comparing apples to apples with what happens.

If you’re not sure how much traffic/revenue your current bid generates, try the experiment feature.

Launch an experiment in which you decrease/increase your bid and see what happens directly.

2) Be on the Lookout for Affiliates (Aggressively)

NO AFFILIATE should be allowed to do any brand bidding. This should be baked into your affiliate program, but even if it is, it can still happen.

Your affiliate network will not proactively check whether affiliates are abiding by the rules, so you must do this for yourself.

3) Campaign Structure for Brand Bidding

When it comes to the campaign structure, there are some easy fundamentals to always follow:

- Search: Branded keywords should always be in their own campaign and should be excluded from all other campaigns proactively (including your DSA campaign).

- Shopping / P-Max: Branded keywords should be excluded from your main campaign(s), and you should run low-priority Standard Shopping campaigns to cover branded traffic.

In 80% of cases, both should run on manual bidding (although some can run Shopping Ads on ROAS target that maximizes revenue – by using experiments – at the highest possible ROAS).

4) Brand and Non-Brand ROAS Should Never Be Aggregated

I’ll die on the hill that you should never combine reporting for brand and non-brand traffic.

This is because it’s not only Google Ads that’s driving brand search volume, so it makes no sense for Google Ads to take full credit for it.

Is there an overlap? Definitely, but that doesn’t mean Google Ads is the be-all and end-all.

We do sometimes report jointly in Savvy, but it’s because we’ve given up trying to get the client onboard.

What About P-Max Data Consolidation?

This wasn’t an issue until 2023. Suddenly, a conversation started around the idea that you should include brand terms in P-Max to allow it to get more insights.

Again, there are levels to this issue:

- New brand with few brand searches? No biggie. Keep it (it might even be beneficial).

- Well-known brand with a lot of brand searches, but just starting out in Google Ads? Fifty-fifty, but you most likely have more to lose than gain.

- Well-known brand with lots of data in your Google Ads account? The waste on branded terms is too high, and your non-brand terms have enough data to not need branded terms.

The problem with including branded terms in your P-Max campaign is that it’ll artificially inflate the ROAS, and you will either end up running ad spend that isn’t incremental, or the brand terms will end up covering for unprofitable ad spend.

Let’s Do The Math

It all comes down to how big of an impact your brand term has on the data in your Performance Max campaign.

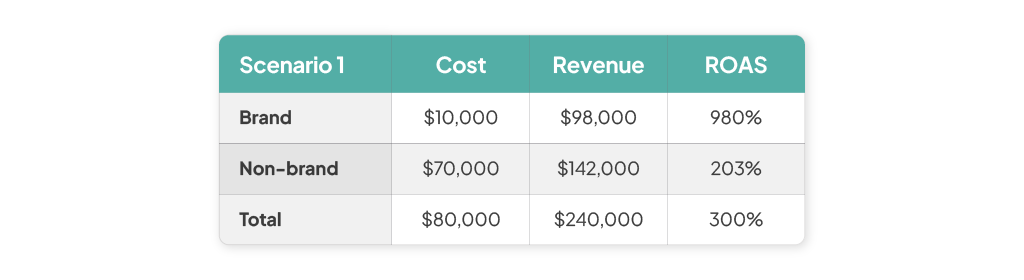

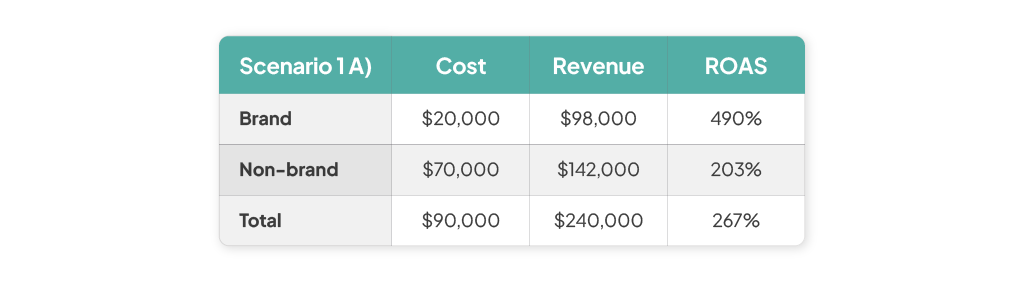

Let’s take two scenarios:

In scenario 1) the ROAS is increased by 50% due to the high revenue coming from brand terms.

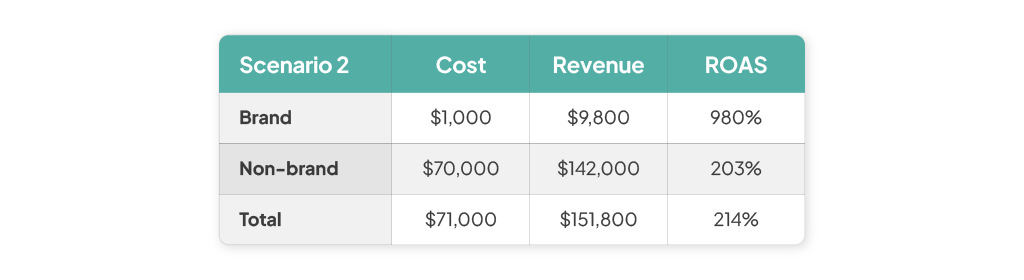

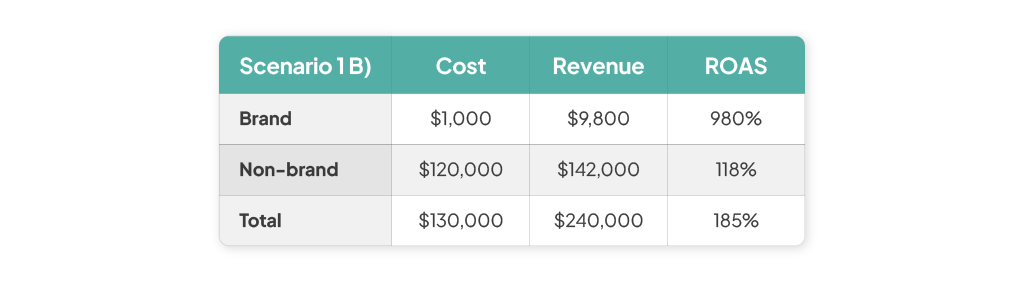

In scenario 2) the ROAS is marginally increased from 203% to 214%.

This is why we all have these discussions on Twitter and LinkedIn but can’t agree.

If you’re running an account in scenario 2, then who cares? Excluding brand is an unnecessary complexity that you don’t have to deal with.

But let’s say scenario 1 looks like this instead:

How do you find out if the $20,000 spent on your brand is the right amount to spend on your brand?

And let’s take another scenario:

Your target is 200% ROAS for Google Ads. The scenario above looks fine. A bit on the low side, but OK.

However, the branded terms are covering for the fact that the entire non-brand effort is unprofitable.

So, in that case, how do you A) come to this realization and B) rectify it?

At this moment, you can’t do so reliably. Yes, you can run scripts to get insights, but outside of applying a new customer goal (which is a difficult metric to work with — see below), there isn’t anything you can do about it, which means you’re better off splitting out your branded traffic anyways. So, why not just start there?

“But I Track New Customers from Branded Terms.”

This is a common objection I get from people who want to push P-Max brand/non-brand consolidation.

It’s a misunderstanding (and it’s often joined by the question, “Why can’t we just use the new customer setting in P-Max?”.

The problem is that brand terms can produce new and existing customers equally.

New customers in your funnel can easily search for your brand term and then convert. That doesn’t mean that your brand term was incremental for you to generate that new customer.

Even if you’re tracking new customers from your branded terms, it doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to run at your New Customer ROAS target.

Again, we go back to the question:

- Are there a lot of competitors for your branded term that you can lose the sale to?

If not, you should aim to bid as low as possible just to be present (or consider completely bowing out of the Google-branded keyword tax).

So, Should You Do Brand Bidding?

Probably.

And you should probably spend less than you do if you’re spending at all.

But as I’ve outlined in this article, it’s not always black and white.

We have very large advertisers with whom we’ve never spent a dollar on branded keywords because it would not be incremental, and it would take from the budget for our non-brand spend, which we know is entirely connected to acquiring new customers.

6 thoughts on “The Real Reason Nobody Agrees on Brand Bidding in Google Ads (incl. P-Max)”

Great article by the way. Have you also ever considered segmenting Brand into 2 campaigns (new vs returning customers)? I’ve heard that Brand tends to have low incremental revenue from Crealytics because a lot of the returning customer would of converted anyways. New customers should be still bided on and possibly returning but with a much lower bid. You can exclude those existing customers through purchase cookies, login clicks and customer lists as well.

Jeg elsker virkelig din måde at forklare på. Du klarede det godt!

Spændende læsning! 🙂

Thanks Andrew, great article. Couple questions… In addition to not linking the Brand Child Account to GA, assuming you have an MCC… would you also suggest not tracking conversions in the child account, so as to not siphon off conv from other child accounts in G Ads?

Correct — No need to track anything in the child account unless you are in a competitive market. We have seen markets where bidding on each other’s brand terms is common or where the brand term is closely connected to generic terms. In such cases it’s still war and the brand-bidding aspect will be more closely related to your regular efforts.